Disciplinary literacies are the reading and writing practices that are valued in a community of practice. They can be thought of as “rules for use,” or the standards that guide students’ participation in the practices of a discipline. These rules are the conventions of a discipline that guide thinking, reading, writing, and talking practices (Shanahan & Shanahan, 2008). When we teach disciplinary literacies, we teach students to read, write, think and talk like members of a discipline. In this post, we discuss how text sets can help us provide our students with a broad perspective and the required background knowledge in a domain and access to texts written for disciplinary insiders that help students begin to move toward independent disciplinary reading.

Disciplines have different ways of using language as part of their work. These differences in language use are called disciplinary literacies or disciplinary discourses. For example, knowing how to read a table and integrate the data presented there with a narrative is essential for scientific reading comprehension. On the other hand, knowing how to read a table is not helpful to literary critics but being sensitive to implicit connotations of the language used in short stories is essential. Our students benefit when we are explicit about the literacy skills required to succeed in our discipline. And for our students to understand how to read like a scientist, they need to have access to texts with tables and data that allow them to practice reading like an expert. Using small excerpts of disciplinary expert text can help enliven disciplinary thinking in your classroom and improve the text sets you may be currently using. (Lupo, Strong, Lewis, Wapole & McKenna, 2018)

The challenge is that most texts that allow students to use disciplinary-specific reading skills are also challenging. Therefore, many publishers create resources to help make informational texts, primary sources, and other complex texts more accessible. For instance, in a math classroom, we may be reading an online resource that provides a video narrative in which the table provided in the text is interpreted for students, providing very few opportunities for students to engage as mathematicians (Weinberg, Wiesner, & Fulmer, 2022). Or we might be reading a version of the poem that uses font formats and callouts to draw attention to poetic language, offering little chance practice the disciplinary reading habits which literary scholars use to make meaning. These texts position students not as disciplinary insiders but instead as perpetual novices for whom significant scaffolds are provided.

This raises a central question: How can our students learn to cultivate these reading skills if the work is done for them by considerate texts? And how can we give access to expert texts without frustrating and discouraging students still developing as readers? This post introduces the concept of disciplinary expert texts and disciplinary pedagogical texts (Galloway, Lawrence, and Moje 2013). We describe why both are important and can help students gain essential reading skills when they are used in our text sets.

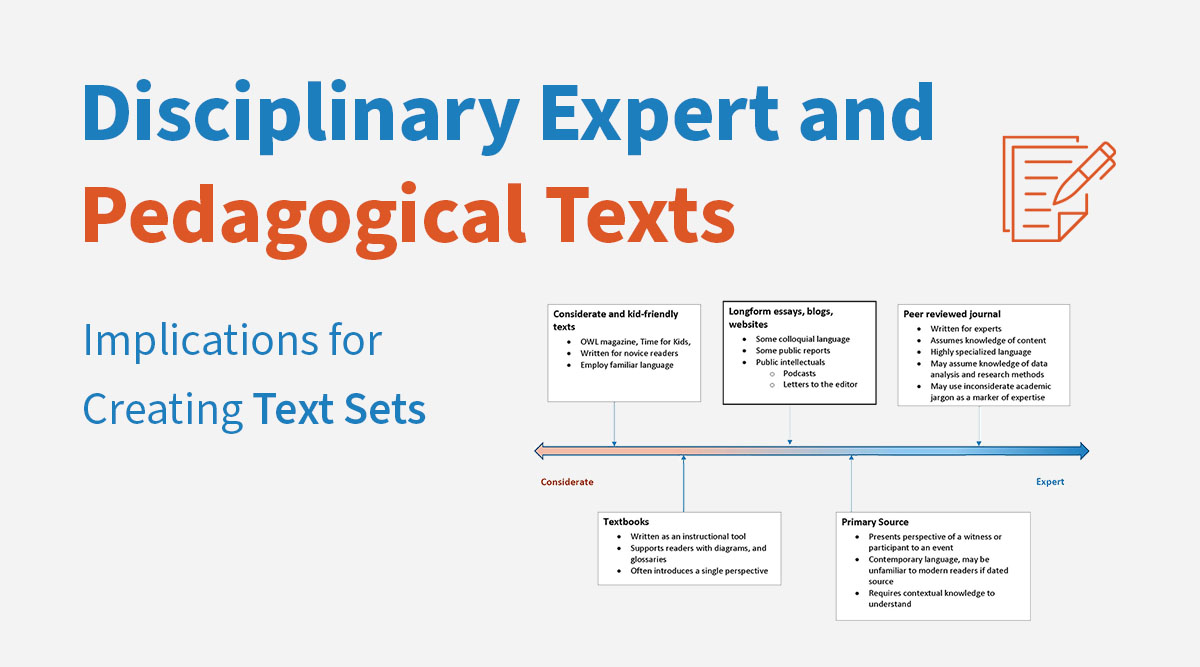

To be clear, it is not only school texts that endeavor to be considerate of their readers. Texts exist on a continuum from more disciplinary to less. Some texts are written for a general audience or to introduce a topic. They do not make assumptions about the readers' background knowledge or position the reader as a disciplinary insider. These texts include popular science articles appearing in newspapers containing supportive infographics, youtube videos that broker disciplinary ideas, and printed resources like TIME magazine for kids. Other texts, such as those written in peer-reviewed journals, books written for a disciplinary audience, or primary source texts, are written by and for experts. These texts assume the reader has expert knowledge and is comfortable using specialized reading skills. Even strong readers may find these texts extraordinarily challenging and not a great way to learn about a new topic.

Thus there is always tension between how expert a text is and how considerate it is for a novice. Using texts written for audiences of disciplinary experts is not without challenge. However, we have come to see how it is possible when close reading is scaffolded by thoughtful lesson plans and clear essential questions. We now believe that both kinds of texts are important and should be considered in every secondary text set.

Disciplinary Expert Texts

These texts are meant to discuss topics only known by people who have studied that topic extensively. For example, researchers who have studied this topic for years usually write a biology article in a journal. They would not expect the average reader to understand their article. Since the writer of expert texts is a member of the discipline, she understands the knowledge readers bring to the content. Disciplinary expert texts will use text forms, diagrams, equations, historical documents, pictures, technical plans, museum artifacts, and other rich resources in disciplinary appropriate ways and assume the reader knows how to understand and integrate these forms. In sum, readers are positioned as disciplinary experts, and as readers take on the identity of a mathematician, social scientists, literary critics, physicists, and other disciplinary experts.

Disciplinary Pedagogical Texts

Disciplinary pedagogical texts are meant to describe topics and concepts to an audience that does not yet have rich content background knowledge or understanding of disciplinary-specific forms. Examples include websites for kids, textbooks, kids magazines, and many of the pedagogical materials we use in our classes. Publishers often designed these texts to support such as brief definitions for unfamiliar words. Online environments may even include videos, translations, and read-aloud options. Readers are assumed to be novices and positioned as such by the writer (Frankel, 2017).

Creative and inexpensive suggestions

What’s evident is that readers cannot engage with disciplinary expert texts and disciplinary pedagogical texts in the same ways. As educators, we need to provide opportunities for both types of engagement. We should use a range of texts in creating our lessons and include both disciplinary expert and disciplinary pedagogical texts. Textbooks portray disciplinary knowledge as static presented by experts who follow rigid patterns. There are stark differences between how scientists actually analyze data and make inferences and the philosophical presentation of science presented in textbooks (Debbie Liu and Grotzer 2009).

Some of the successful examples we've seen include the following:

- A social studies teacher reads small portions of an adult translation of Homer to supplement the more considerate translation they read with the class. The section they read includes the story about how Polyphemus is tricked into getting drunk by Odysseus and ends up throwing up. Because Polyphemus had eaten several of Odysseus's men the night before, he threw up human remains. GROSS! The teacher emphasizes that the actual poems were action-packed and highly engaging to their hearers and tries to help the students get closer to the experience of the epic audience. "He spoke and slumped away and fell on his back, and lay there with his thick neck crooked over on one side, and sleep who subdues all came on and captured him, and the wine gurgled up from his gullet with gobs of human meat."

- During a unit on evolution, a science teacher shares figures from one of Darwin's experiments (Darwin 1863). She emphasizes the detailed work involved in scientific discovery and why careful data collection, replication, and peer review are cornerstones of the scientific method. She uses these texts to help her students understand the reasons for the literacy norms in science with content that aligns with her content goals.

Both of these examples use small samples of authentic text to help students develop an insiders perspective on disciplinary reading.

When designing text sets, teachers should consider if any particular text is more of an expert text or more of a pedagogical text. We should consider this dimension when we design our lesson plan and think about how to sequence these texts. We might begin with those that are designed for novices to a discipline and then examine how that same information is conveyed in a text written for an audience of disciplinary experts. As our students turn to express their thinking in writing, we may move between having them express these understandings for other students, younger children or other groups of non-experts to writing texts as disciplinary experts. Expert texts allow us to demonstrate how our discipline works, give our students a sense of accomplishment and provide opportunities to share our enthusiasm for our discipline.

Our teaching is about our students, not us. But sharing texts that we love and get excited about gives us a chance to share our passion and help the student understand the importance and impact of our discipline. It can also give us a chance to "geek out" and invite our students to join the fun. Giving our students access to disciplinary expert texts can help them feel confident with a range of text difficulties and may provide unexpected opportunities for building background knowledge.

References

Darwin, Charles. 1863. "On the Existence of Two Forms, and on Their Reciprocal Sexual Relation, in Several Species of the Genus Linum." Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. Linnean Society of London 7 (26): 69–83.

Liu, Y., and Tina A. Grotzer. 2009. "Looking Forward: Teaching the Nature of Science of Today and Tomorrow." In Fostering Scientific Habits of Mind, 9–36. Brill.

Lupo, S. M., Strong, J. Z., Lewis, W., Walpole, S., & McKenna, M. C. (2018). Building Background Knowledge Through Reading: Rethinking Text Sets. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy: A Journal from the International Reading Association, 61(4), 433–444. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.701

Frankel, K. K. (2017). What does it mean to be a reader? Identity and positioning in two high school literacy intervention classes. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 33(6), 501–518.

Galloway, E. P., J. L. Lawrence, and E. B. Moje. 2013. "BC5. Research in Disciplinary Literacy: Challenges and Instructional Opportunities in Teaching Disciplinary Texts." In Adolescent Literacy in the Era of the Common Core:From Research into Practice, edited by J. Ippolito, J. L. Lawrence, and C. Zaller. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Educational Press.

Shanahan, T., & Shanahan, C. (2008). Teaching disciplinary literacy to adolescents: Rethinking content-area literacy. Harvard Educational Review, 78(1), 40–59.

Weinberg, A., Wiesner, E. & Fulmer, E.F. Didactical Disciplinary Literacy in Mathematics: Making Meaning From Textbooks. Int. J. Res. Undergrad. Math. Ed. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40753-022-00164-1